Our defense against pathogens and cancer relies on the remarkable skills of leukocytes to patrol all nooks of the body. Leukocytes become highly deformed when circulating in the bloodstream, they can decide to adhere to blood vessel walls, they can move autonomously through tissues, and they can aim at targets by sniffing out environmental cues. However, these feats rely on exquisite mechanisms that are only partially understood. Our strategy is to analyze quantitatively these mechanisms of leukocytes navigation using in vitro minimalist experimentations based on ad hoc microengineering and optical microscopy techniques. A fundamental aim is to decipher the mechanisms, and an applied aim is to transfer our approaches to medical issues to shed light on physiopathological mechanisms and design diagnostic tools.

LEUKOCYTE DEFORMABILITY: Acute respiratory syndrome triggered in the microcirculation

With P Bongrand, P Robert, (LAI); JM Forel, L Papazian (Critical care unit, Marseilles hospitals)

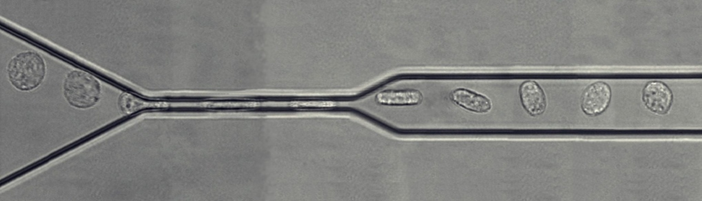

We have developed microfluidic tools to explore the passage of circulating leukocytes through narrow constrictions mimicking lung blood capillaries (Biophys J 2009, Lab Chip 2010). We designed a microfluidic rheometer yielding quantitative measurements of cells viscosity (Biomicrofluidics 2013). A diagnostic tool was also built and tested at hospital to assess rigidification of leukocytes in whole blood samples (Lab chip 2013). A medical study of leukocytes adhesiveness and stiffness with serum of ARDS patients allowed for the identification that cytokines trigger ARDS by a massive arrest in the lung microcirculation of stiffened leukocytes (Critical Care 2016).

Figure 1: Microfluidic micropipette. Montage d’images de microscopique montrant le passage d’un leucocyte dans une constriction simple de largeur 4 µm.

Friction of in confined environments. (Coll J Bico, MC Julien ESPCI, Paris) The quantitative analysis of cells friction in microchannels developed for the cell microrheometer was also applied to the physics of droplets/bubbles traveling in confined environments (PRL 2015, Lab Chip 2016, J Fluid Mech. 2018, Biophys J 2021).

LEUKOCYTE PROPULSION : swimming and molecular paddling

with MP Valignat (LAI); C Misbah, A Farutin (LiPhy, Grenoble); S Tlili (IBDM, Marseille)

Related publications: Biophys J 2020, Biophys J 2021, Biol Cell 2021

Highlights: Biophysical Journal , Science, Eurekalert, Science&Vie

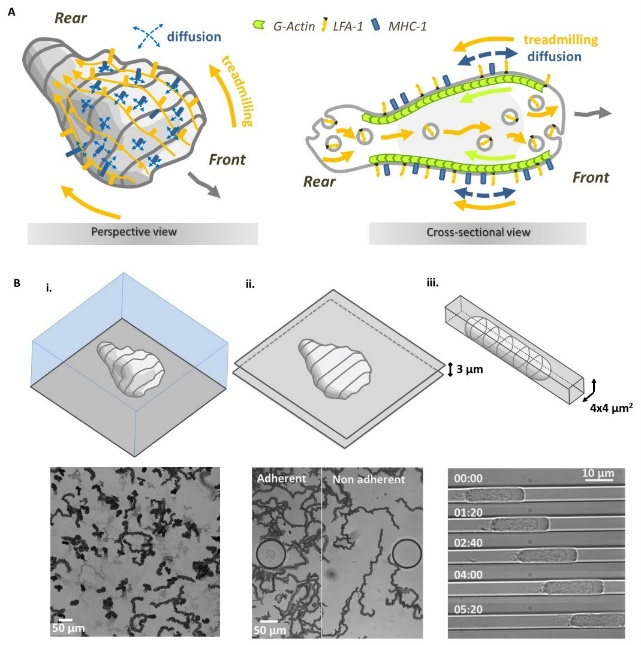

The most widely studied migration mechanisms involve mesenchymal cells (slow, highly adhesive, matrix-degrading), such as fibroblasts. Our focus here is leukocytes, which are often amoeboid cells (fast, not very adhesive, not matrix-degrading). Unlike mesenchymal cells, amoeboid cells can migrate without adhesion to a substrate, provided they are confined by a solid environment. In this context, we have shown that immune cells can also migrate without adhesion and without a substrate: they literally swim. In collaboration with theoreticians (C Misbah, A Farutin, LiPhy, Grenoble), we have quantitatively validated an original mechanism of propulsion by molecular paddles (Figure 2).

This work revisits some dominant ideas in the field of cell migration by proposing 1- that leukocytes do swim, 2- that swimming by cell deformation is not effective for leukocytes, and 3- that retrograde movement of the membrane is propulsive via protein paddling.

Figure 2: Model of motility by molecular paddling and recycling of paddles. (A) Schematics explaining the model of molecular paddles to propel lymphocyte swimming. Membrane protein ‘paddles’ (orange) are pulled to the rear of the cell by the cell-internal actin cytoskeleton (green) and recycled by internal vesicular trafficking (grey bubbles). These paddle molecules have a propulsive effect. Other membrane proteins (blue) not linked to actin diffuse randomly across the cell surface, slowing down migration. (B) The molecular paddle model discards cell arrest due to “frictionless” medium. Lymphocytes migrate (i) onto a non-adherent surface, (ii) between two non-adherent walls, and (iii) into a non-adherent constriction, by friction with the substrate.

LEUKOCYTE GUIDANCE

The ability of cells to orient themselves according to external stimuli is at the heart of essential functions of the living world. It is a priori the result of an evolutionary process that has led to the construction of sophisticated mechanisms to sense external stimuli, process internal biochemical signals and reorient the motility machinery. We are interested in directed migration by physical cues (flow, adhesion) and chemical cues (soluble or anchored).

Rheotaxis: directed migration against a flow by passive mechanism

with MP Valignat (LAI); S Gabriele (U Mons, Belgium)

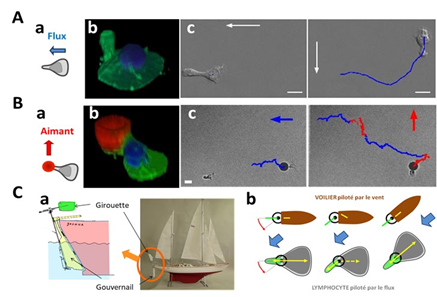

We made the striking observation was that lymphocytes direct their migration against a hydrodynamic flow, like salmon swimming upstream (Biophys J 2013). While this phenomenon seems to derive from an active response of the cells to oppose an external force, we have explained it by a passive mechanism in which the tail of the cells acts like a windvane (Nat Comm 2014) (Figure 3). The term passive describes here a mechanosensory mechanism without mechanotransduction. This minimalist mechanism can also explain a complex phenomenon of biphasic state of cells going with and against flow when two types of adhesion molecules are involved (integrins LFA-1 and VLA-4) (Biophys J 2020 ; Front Bioeng Biotech 2021). cRecently, a quantitative model without adjustable parameters (Roly-poly model) was successfully applied to the rheotaxis of fish keratocytes, in which cell direction is set by their morphology (PNAS 2022; Actu CNRS 2022).

Figure 3: Passive rheotaxis model (A) Lymphocyte guidance under flow. (a) Schematics of a lymphocyte crawling on a flat surface under flow. (b) 3D image of a lymphocyte showing the nucleus in blue and the membrane in green. The uropod, which protrudes sharply upwards at the rear of the cell, acts as a weathervane in our model. (c) In a 90° rotating flow, a cell changes direction in less than a minute. The white arrow indicates the direction of flow, the blue line the trajectory of the cell. Scale bar 10 µm. (B) Remote control of lymphocytes via tail actuation. (a) Schematics of a lymphocyte with a magnetic bead stuck to its tail (red) is manipulated remotely with a magnetic force. (b) 3D image of a lymphocyte showing the nucleus in blue, the membrane in green and the magnetic ball in red. (c) Alternatied actuation in a perpendicular fashion “pilot” cell remotely on a staircase trajectory. Scale bar 10 µm. (C) Passive windvane self-steering mechanism. (a,b) “Sailboat windvane self-steering system”. A windvane (green) detects the wind direction and “transmits” it to the rudder (yellow) which steers the sailboat (drawing adapted from B. Moitessier “The long way”). (b) Similarly, the lymphocyte tail (green) detects the direction of flow and “transmits” the direction to the cell’s forward-backward polarization regulating mechanism (yellow).

Reverse Haptotaxis: directed migration towards less adhesive substrates

with MP Valignat (LAI); JF Rupprecht (CPT, Marseille) ; V Studer (IINS, Bordeaux)

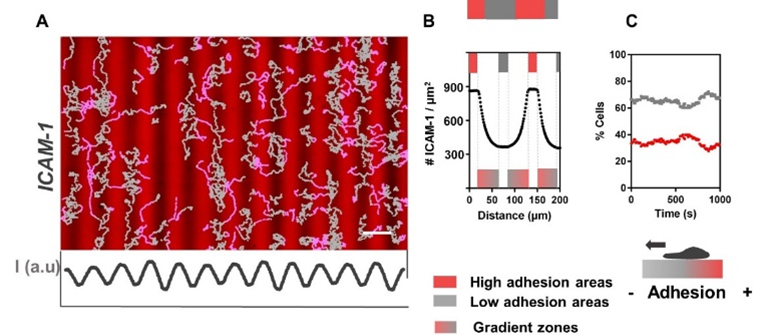

Adhesive haptotaxis has been known and studied since the 1960s for various mesenchymal cells. Our work reports the first evidence of adhesive haptotaxis with amoeboid cells, despite the fact that leukocyte migration, as previously described, does not depend on adhesion (they swim). Even more surprisingly, while mesenchymal cells have always shown an orientation towards the most adherent zones, our work has shown that lymphocytes, under certain conditions, orient themselves towards the least adherent zones. This counter-intuitive phenomenon has been dubbed ‘reverse adhesive haptotaxis’ (JCS 2020) (Figure 4). From a mechanistic point of view, the basis of adhesive haptotaxis is still debated for mesenchymal cells, and the mechanism of reverse haptotaxis remains even more mysterious (see outlook).

Figure 4: T lymphocyte ‘reverse’ haptotaxis. (A) Fluorescence images of repeated gradient patterns of ICAM-1 molecules (red), ligands for LFA-1 integrins. (B) Profiles of ICAM-1 ligands (C) Percentage of cells on less (grey) and more(red) adherent areas as a function of time. At equilibrium, lymphocytes converge towards less adhesive areas (reverse haptotaxis).

Chemotaxis: deciphering lymph node traffic and beyond

With MP Valignat (LAI); M Bajenoff (CIML, Marseille)

Chemotaxis is the best-known and most studied cell guidance mechanism. It occurs in most cell types, and numerous specialized receptors have been identified for many substances, cells and functions. However, the biochemical cascades that enable the cell to process the external signal and decide on its orientation are still incompletely characterized, both qualitatively (natures of the intermediate proteins of the signaling cascade) and above all quantitatively (constants of the chemical equilibria of the cascade). Experimental tools have long been lacking to characterize intracellular signaling quantitatively and dynamically. Microfluidics and biosensors now make it possible to control chemical stimuli and record the associated phenotypes.

We have developed several microfluidic systems enabling quantitative spatio-temporal control of soluble gradients of chemokines in the absence of flow (Lab chip 2020) and ongoing projects aim at elucidating the traffic of T lymphocytes in lymph nodes (iScience 2023).

Biomedical transfer

With P Robert, MP Valignat (LAI) C Chabanon (IPC) P Rihet (TAGC)

We are currently working on the adaption of microengineered and optical devices for functional phenotyping of leukocytes properties in the context of allergy, infections and cancer immunotherapies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.